Always be Poking and Experimenting (9/30)

I'm writing 30 posts in 30 days. This is number 9.

I read a lot. Newsletters, books, articles, blogposts, and even listen to podcasts. One thing I read last week that grabbed me was this newsletter by the author of Range, David Epstein. And I quote the key paragraphs below:

One of my favorite thoughts in Range came from Herminia Ibarra, a professor of organizational behavior at London Business School, who studies how people make successful (and unsuccessful) career transitions: “We learn who we are in practice, not in theory.”

Ibarra pushed back against a formidable and lucrative industry that promises to tell you exactly who you are and what you should be doing if you just take this quiz, or follow that simple program. She was bothered by conventional-wisdom articles like one in the Wall Street Journal[on “the painless path to a new career,” which promised that the secret is simply forming “a clear picture of what you want” before taking action. In her research, and in her book Working Identity, Ibarra showed that this is approximately the polar opposite of sound advice.

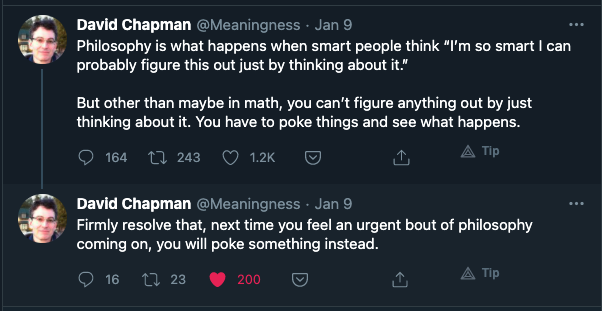

In turn, this reminds me of a pair of my favorite all-time tweets by David Chapman

In case the tweets get taken down

I am a fan of philosophy. I do well in areas when reflection, introspection, and abstraction (I shorthand these as RIA) are highly productive. But my mistake was to carry that preference for such head-first skillsets into areas when they are less useful. From my experience, most areas in life do less well when you rely solely on RIA skills.

Don’t wait to take action after we get the theory pat down

Often the biggest fallacy is that we want to figure it out in our plans first before we take action. I’m not against this approach per se. But, the danger is we can get so wrapped up in the plans, the reading of books and all the RIA busywork, that we end up procrastinating on taking actions. Reading books is a great way to run away due to fear. I know that problem very well.

I’m slowly correcting this. You’re, in fact reading a piece, that was due to a whim to write 30 pieces on substack for 30 straight days. I was over-planning and avoiding the very act of writing itself. I’m not convinced I’m actually getting better at writing itself. What I have learned a lot from this exercise is the day-to-day time and project management that underpins so many issues with my work, side projects, and life in general. To avoid getting stuck in coming up with ideas, I realized one thing that works well is to simply dump every possible idea into the drafts.

This piece you’re reading was simply borne out of a feeling immediately after I read the Epstein newsletter. “Oh, that would make a good start for a possible writing piece!” And then I copied pasted the link, the key paragraphs in a substack draft. That was it. It took less than 30 seconds in total.

And now, you’re reading this piece. After I took the draft several days later, and kept elaborating.

If you’re a heavy reader like me, chances are you have similar issues of reading too much, theorizing too much as well. I leave you with a useful framework Jeff Bezos of Amazon use for making decisions under pressure.

I quote

Never use a one-size-fits-all decision-making process. Many decisions are reversible, two-way doors. Those decisions can use a light-weight process.

Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive.

Using the phrase “disagree and commit” will save you a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this, but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes.

Recognize true misalignment issues early and escalate them immediately. Teams sometimes have different objectives and fundamentally different views. They simply aren’t aligned — and no amount of discussion, no number of meetings will resolve that deep misalignment. Without escalation, the default dispute resolution mechanism for this scenario is exhaustion. Whoever has more stamina carries the decision.

High Velocity, High Quality Decisions

All these are great points for making decisions. I want to focus on the first point where if it was repeated in an earlier Amazon shareholder letter. Often, people like me who want to read up on prior art, theorize like mad, and get the plans all lined up, the key is to make great quality decisions. The drawback is it becomes slow to get started. If we swing to the opposite extreme, we can make hasty, ill-advised decisions that can be easily avoided with a quick google search.

Bezos’ point was while making high quality decisions is important, we should not treat all decisions are irreversible or come with incredible high costs to start. The best of both worlds was to come up with high-velocity, high-quality decisions. One way to achieve that was to boldly go forward with reversible decisions. Taking actions always generates new information.

My working framework for now is something like this:

Pick a hairy, ambitious goal

Break it down into a series of intermediate goals

Pick the nearest intermediate goal and ask, “can this be formatted as a single, reversible decision that generates new, useful information that informs the rest of the approach?”

If yes, then let’s jump into it as Bezos recommended. If no, then repeat steps 2 and 3 with this intermediate goal.

Repeat until we hit one good next decision to take that’s reversible and can provide useful information when taken.

I’m basically experimenting with this working theory. I’m looking for a way to grow a newsletter audience of 10k. But, I still haven’t figured out a niche to write for. Or even if I want to. Several iterations of the above, I land at the question, “can I write regularly for 30 days?” Which basically turned into this newsletter you’r reading.

If you’ve read this far, thank you 🙏

There are still gaps with this working framework. One key question I’m still figuring out is how long to persist with a reversible decision if no new information is forthcoming. I might come back and write a follow up post to answer that question in a future piece.

Talk to you then!