Notes on Objective Paradox Part I: Think In Search Space

Highlights and commentary of Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective by Joel Lehman and Kenneth O. Stanley

I commented at Unknown Unknowns post "Niches get Stitches" recently, drawing parallels between the post and the Why Greatness Cannot be Planned book.

As I kept adding more and more highlights from the book in the comment, I realized I would be better off writing standalone highlights-and-commentary posts instead.

Why This Matters For Entrepreneurial Engineers

Starting a new business initiative and keeping it running is hard.

The kind of hard that seems more like the difficulty of great accomplishments cited in the Why Greatness Cannot be Planned (henceforth known as Why Greatness) book.

And the authors of Why Greatness argue that setting ambitious objectives are counterproductive to achieving them.

Highlights with Commentary

Here are my highlights from the book’s first four chapters (total eleven). In total, I highlighted 28 snippets that stood out—along with some commentary.

1/ "This book was born from a radical idea about artificial intelligence (AI) that unexpectedly grew to be about much more.

…Usually these algorithms have explicit goals and objectives that they’re driven to achieve. But I began to realize that the algorithms could do amazing things even if they had no explicit objective—maybe even more amazing than the ones that did have an objective.

…I started to realize that the insight wasn’t just about algorithms, but also about life. And not just life, but culture, society, how we drive innovation, how we plan for achievement, our interpretation of biology—the list just kept expanding."

Joel Lehman is a machine learning research scientist. Kenneth Stanley leads a team at OpenAI as research science manager and even has his own wikipedia page.

Generalizing insights outside of the field they originate from can be dangerously sketchy. A classic example is the suspicious claims from New Age authors when they tried to extrapolate ideas from quantum physics.

The authors have great credentials as scientists, so they have a higher bar for what counts as true than your average person. Extrapolating AI concepts to general career planning would be the kind of sketchy generalizing I’m typically suspicious of.

But, I take scientifically trained people more seriously than laypeople. So I’m willing to give more benefit of the doubt.

2/ "A lot of effort and resources are spent measuring progress towards these objectives and others like them. There’s an assumption behind these pursuits that isn’t often stated but that few would think to question: We assume that any worthy social accomplishment is best achieved by first setting it as an objective and then pursuing it together with conviction.

…Everyday successes like these mislead us into believing that setting objectives works well for almost everything. But as objectives become more ambitious, reaching them becomes less promising—and that’s where the argument becomes most interesting. Some objectives are anything but certain."

The book’s thesis is that for highly ambitious achievements or those with high degree of uncertainty, setting them as objectives paradoxically decreases your chances of achieving it. An "objective paradox" if you will.

I will pair this book with Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr. Both are former Amazon executives who worked there in the early years. And their approach sounds, on the surface, the opposite of what Stanley and Lehman suggest here.

Since I started a Notes on Objective Paradox, I’ll also have to do a Notes on Working Backwards in future as well.

3/ "It’s useful to think of achievement as a process of discovery. We can think of painting a masterpiece as essentially discovering it within the set of all possible images. It’s as if we are searching through all the possibilities for the one we want, which we call our objective.

Of course, we’re not talking about search in the same casual sense in which you might search for a missing sock in the laundry machine. This type of search is more elevated, the kind an artist performs when exploring her creative whims. But the point is that the familiar concept of search can actually make sense of more lofty pursuits like art, science, or technology.

All of these pursuits can be viewed as searches for something of value. It could be new art, theories, or inventions. Or, at a more personal level, it might be the search for the right career."

Let’s assume that choosing an entrepreneurial path for your career or lifestyle is non-negotiable. Choosing the right specific entrepreneurial endeavor that meets your ambitions fits the kind of elevated search mentioned here.

Search Space, Stepping Stones, and Adjacent Possible

4/ "…we can think of creativity as a kind of search. But the analogy doesn’t have to stop there. If we’re searching for our objective, then we must be searching through something. We can call that something the search space—the set of all possible things.

…pretend you wanted to paint a beautiful landscape—so that’s your objective.

If you’re experienced in landscape painting, it means that you’ve visited the part of the room teeming with images of landscapes. From that location, you can branch off to new areas full of landscapes that are still unimagined.

But if you’re unfamiliar with landscape painting, unfortunately, you’re unlikely to create a masterpiece landscape even if that’s your objective. In a sense, the places we’ve visited, whether in our lives or just in our minds, are stepping stones to new ideas.

…stepping stones are portals to the next level of possibility. Before we get there, we have to find the stepping stones."

As a software engineer, the analogies of search space and stepping stones are familiar to me. I, too, have to search through a space of possible solutions when trying to solve difficult problems in the systems I build for customers.

As for the stepping stones analogy, it reminds me of the Adjacent Possible concept. Which I first learned from Steven Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation. Even though he took the concept from Stuart Kauffman who introduced it to explain how biological systems evolve into more complex systems “by making incremental, relatively less energy consuming changes in their make up”.

Put together, the idea is the adjacent possible are the stepping stones between what you currently know/possess and the remote possible you want to get to.

5/ "Objectives are well and good when they are sufficiently modest, but things get a lot more complicated when they’re more ambitious. In fact, objectives actually become obstacles towards more exciting achievements, like those involving discovery, creativity, invention, or innovation—or even achieving true happiness. In other words (and here is the paradox), the greatest achievements become less likely when they are made objectives.

…if the paradox is really true then the best way to achieve greatness, the truest path to “blue sky” discovery or to fulfill boundless ambition, is to have no objective at all."

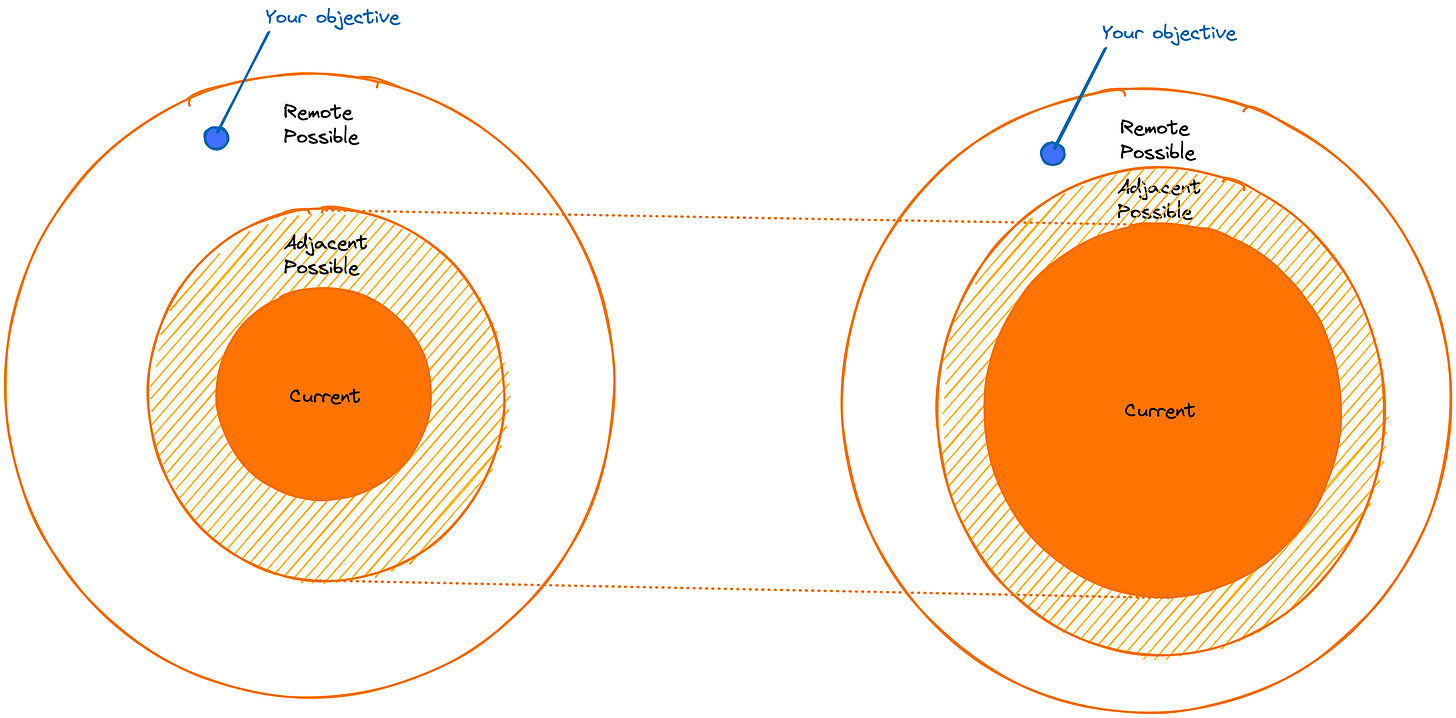

I’m reusing the same 3 concentric circles from the previous commentary.

There are two kinds of objectives that are in the remote possible: those that you can conceive and those that you cannot. Regardless if they are conceivable, the path to them are highly uncertain. Because even after expanding your current sphere to include the original adjacent possible, your objective may still not be in the new adjacent possible.

In my model, the characteristics of any objective that fall under each of the 3 spheres are:

Current: any objective here is conceivable and definitely within grasp. Within grasp as in doable within your capabilities.

Adjacent Possible: any objective here is conceivable and theoretically but not definitely within grasp.

Remote Possible: any objective here may be conceivable or inconceivable, but definitely not within grasp.

6/ "Even after vacuum tubes were first discovered, no one would realize their application to computation for over 100 years. The problem is that the stepping stone does not resemble the final product. Vacuum tubes on their own just don’t make people think about computers. But strangely enough, as history would have it vacuum tubes are right next to computers in the great room of all possible inventions—once you’ve got vacuum tubes you’re very close to having computers, if only you could see the connection. The problem is, who would think of that in advance? The arrangement, or structure, of this search space is completely unpredictable.

…If you were like Charles Babbage in the 1820s and wanted to build a computer, you wouldn’t dedicate the rest of your life to refining vacuum tube technology."

The authors went on to cite more such examples of stepping stones and their more interesting counterparts throughout the history of great inventions. The point here is to bolster two separate ideas:

in the sphere of remote possible there are inconceivable objectives the adjacent possible can lead to. This is the situation exemplified by the line, “Vacuum tubes on their own just don’t make people think about computers.”

even if an objective in the remote possible is conceivable, the path to get there may be inconceivable because (some of) the intermediate steps themselves are also inconceivable. This is the situation exemplified by the line, “If you were like Charles Babbage in the 1820s and wanted to build a computer, you wouldn’t dedicate the rest of your life to refining vacuum tube technology.”

7/ "It often turns out that the measure of success—which tells us whether we are moving in the right direction—is deceptive because it’s blind to the true stepping stones that must be crossed. So it makes sense to question many of our efforts on this basis. But actually the implications are even more grave than just questioning particular pursuits and their objectives. At a deeper level, we might ask why we think ambitious pursuits should be driven by objectives at all."

8/ "As with all open-ended problems in life, the stepping stones are unknown. So when you go out into the uncertain world sometimes it may be wise to hitch a ride with serendipity. Being open and flexible to opportunity is sometimes more important than knowing what you’re trying to do.

…You might think these kinds of stories only apply to the luckiest of the lucky. But serendipity isn’t actually so picky. A peer-reviewed study found that nearly two thirds of adults attribute some aspect of their career choice to serendipity. As one participant put it, “I happened to visit an animal hospital and became interested in veterinary medicine.” You never know what hidden passion you might unexpectedly discover."

My best entrepreneurial result came about because I went to the birthday party of a secondary school classmate I haven’t seen in ages. On a whim. He subsequently introduced me to my highest revenue-generating customer of my career so far.

I’m sure many people in different domains can point to turning points in their careers that are similarly unplanned and serendipitous. The two thirds of adults attributing some aspect of career choice to serendipity1 is a number too big to dismiss.

9/ "As one large survey revealed, “actions such as volunteering, joining clubs and generally making contact with other people and groups are likely to increase a client’s chances of an unplanned experience2.” Note the emphasis on unplanned experience. This isn’t the usual attempt to figure out the best job and pursue it as an objective. It isn’t an impersonal test designed to categorize you into a particular box from a few multiple choice questions. Instead it suggests that you should embark on a search for possible stepping stones without any particular destination.

The beauty of this non-objective principle is that it’s not only about careers. It can apply to almost anything that involves searching for something, which covers an enormous range of activities. Because the stepping stones that lead to the greatest outcomes are unknown, not trying to find something can often lead to the most exciting discoveries (or self-discoveries). This same theme of finding without trying to find will emerge repeatedly throughout this book everywhere from computer simulations to educational systems."

That last paragraph about how the framing of going through search space applies to more than just career planning and AI is the biggest claim made from this book. It might be due to recall bias, or a bias towards novel, surprising experiences, but I’ve always found my best results often come from paths that are a little unplanned.

It’s not nice to admit that because that means I can never fully own my achievements. There’s always an element of luck involved. Either I get less rigorous with my intellectual honesty or I have to get over my ego. I’m choosing the latter.

10/ "While the idea that not looking can be the best way to find is strange and perhaps a bit zen, it does lurk already in some corners of our culture. As Loretta Young said, “Love isn’t something you find. Love is something that finds you.” As one of those great elusive objectives that almost all of us seek, it’s easy to relate to the deceptive search for love. But the funny thing is that almost any ambitious objective could be substituted for the word “love” in the wisest statements uttered on the topic. We just seem to have carved out this small niche, the search for love, where we acknowledge the paradox of ambitious objectives. As D.H. Lawrence put it, “Those that go searching for love, only manifest their own lovelessness. And the loveless never find love, only the loving find love. And they never have to seek for it3.”

…

For example, one day Grace Goodhue was watering flowers only to look up and see Calvin Coolidge in the window shaving with nothing on but underwear and a hat. Luckily for him, she laughed, catching his attention4. It’s unlikely that the future Ms. Coolidge ever targeted men who shave in their underwear, or that future President Coolidge ever thought his best moment would involve being caught almost naked. But then again, the unplanned is often the best plan of all. At least in the domain of romance, we all have some experience with the paradox of ambitious objectives. After all, what could be more ambitious than seeking lifelong happiness?"

11/ "Indeed, psychologists have noted that children need time to explore without specific tasks or objectives set for them by adults56]. Sometimes the term unstructured play is used to describe this kind of activity. Maybe adults need it too."

I’ve always liked learning. I have paid for a lot of online courses in the past and expect to do so into the future. I signed up for a 12-week long Dale Carnegie communication weekly workshop that will run from end January to April 2023.

I’m also literally writing this article in the middle of a trip in Japan to learn how to snowboard.

From the past, I have burnt out from being overly scheduled. Playing Tetris with my schedule did not make me more efficient. It made me more fragile. This snowboarding trip once again reminded me the importance of respecting my minimal requirement of "space" I need to actually acquire a skill. Another separate essay to cover in the future as well.

12/ "YouTube was first envisioned as a video dating site7. But when was the last time you found a date through YouTube? Its founders pivoted to video sharing, and the results speak for themselves.

…the photo sharing service Flickr was originally a smaller feature of a bigger social online game (that itself was inspired by playing an unrelated game about virtual pets)8.

… the (now) video-game company Nintendo also took a winding path to its success. Founded in 1889, for years Nintendo made a modest profit selling traditional Japanese playing cards. Later in the 1960s, as the playing card market collapsed, the company nearly went bankrupt trying out new business ventures like running a taxi service, building short-stay “love hotels,” manufacturing instant rice, and selling toys. The manager of the new toys and games division, Hiroshi Imanishi, hired a group of amateur weekend tinkerers to brainstorm products. When one of the tinkerers created an extendable mechanical toy hand, Hiroshi was impressed and released it as the “Ultra Hand.” The product’s huge commercial success prompted the company to abandon its non-toy ventures. Later Nintendo began to explore electronic toys, eventually leading it to become the iconic video game company behind “Super Mario Brothers9.”

If you take one thing from this chapter, perhaps it should be that you have the right to follow your passions."

I’m always a little bit suspicious of the "follow your passions" thesis. It sounds overly simplistic. There’s also the tendency to conflate passions with hedonistic pleasures.

But, I can certainly accept the idea that using what you’re interested in as a compass for going through a search space. Given that objective-based search isn’t as effective as it seems.

From a career point of view, some of your endeavors MUST pay off. If not immediately, at least eventually.

Nobody has a limitless budget to pursue their passions forever. Eventually, some of these searches need to pay off in order to fund more such searches. A virtuous career cycle for the perpetually curious.

13/ "If you take one thing from this chapter, perhaps it should be that you have the right to follow your passions. Even if they deviate from your original plans or conflict with your initial objective, the courage to change course is sometimes rewarded handsomely.

Another important implication is that not everything in life requires an objective justification. If you had a choice either to attend a prestigious law school or to join an art colony and chose the latter, your family and friends might have some questions: “Why did you give up such a lucrative career for something so uncertain? What are you trying to accomplish?” Instead of struggling to formulate some kind of objective justification that explains how you have the whole thing completely planned out, perhaps the best answer is that no one knows the stepping stones that lead to happiness. Yes, law school may reliably lead to money, but happiness (perhaps for you) is a more ambitious end, and something about that colony feels closer to it. Of course life is full of risk and some choices indeed won’t work out, but few achieve their dreams by ignoring that feeling of serendipity when it comes. You can simply tell your friends that you know a good stepping stone when you see one, even if (like everyone) you don’t know where it leads.

Whether you’re looking for a career, for love, or trying to start companies, there is ample evidence that sticking to objectives just isn’t part of the story in many of the biggest successes. Instead, in those successes there is a willingness to serve serendipity and to follow passions or whims to their logical conclusions."

The emphasis in this quote are all mine.

One thing I like to highlight is, even if the the idea "all the biggest achievements come from following your whims to their logical conclusions" is true, doing that in itself is NOT a guarantee of success.

But, for some of us, accumulating enough resources and capital (monetary and other kinds) can help make it easier to go after these passions. Especially those that are more challenging, with a lower certainty of payoff, or simply take longer to see results.

Another point to add is how some of the handsome rewards you read about other people serving their serendipity can lead you astray. High risks, high rewards games tend to attract gamblers.

I’ve made mistakes both ways.

I’ve made uninspiring (to me) career choices because they are easier to explain to the people around me. It takes a certain courage to tell people you “know a good stepping stone when you see one” especially when it’s not conventionally appealing. I’ve also made bad moves that seem more like a gambler’s desperation for big wins.

Keeping an open mind while listening to your heart is a tricky balance.

PicBreeder

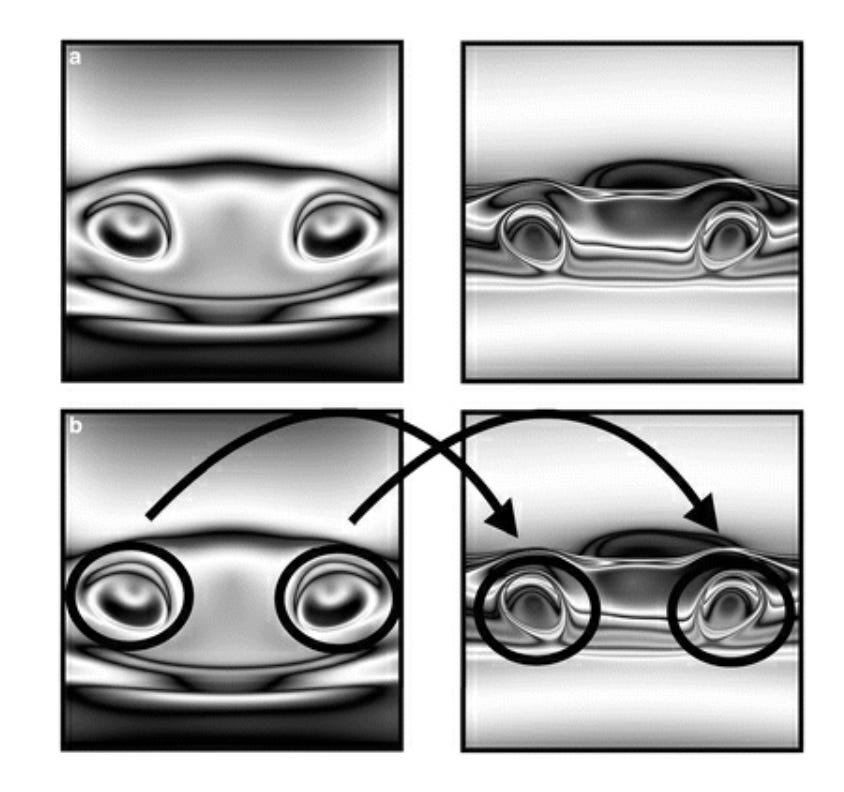

14/ "In 2006, we had developed a new kind of artificial picture DNA that produced more rich, meaningful images (which you will soon see) than were possible before. But more importantly, this new project, which would become Picbreeder, included another ingredient that made it particularly interesting: Any internet user could continue breeding images that were bred by previous users.

… It turns out that after 20 generations or so (i.e. after choosing parents 20 times in a row), most people simply can’t continue concentrating. But evolution works best over many generations, and 20 isn’t enough to produce really interesting pictures.

… Make Picbreeder into an online service. That way, users could share images they had previously evolved with other users, who could then continue breeding them. In other words, if you evolved a triangle on Picbreeder, you could publish it to the website, and then someone else could continue breeding it and perhaps discover an airplane. In Picbreeder, this kind of handoff from one user to another is called branching. The great thing about branching is that it allows breeding to continue far beyond the 20-generation limit."

This is the research project that eventually led to this book being published.

15/ "Now here’s where the story gets interesting. Say, for example, that you’re in the mood to evolve a picture of the Eiffel Tower. One thing you might think is that if you visit Picbreeder and just keep choosing images to breed that look increasingly like your objective (the Eiffel Tower), eventually you’d find it. But interestingly, it doesn’t actually work that way. It turns out that it’s a bad idea to set out with the goal of evolving a specific image. In fact, once you find an image on Picbreeder, it’s often not even possible to evolve the same image again from scratch—even though we know it can be discovered!"

Reproducibility is an issue most of the self-improvement advice givers don’t realize.

Many times for credibility reasons, they cite their own (usually one-off) great achievements. But, they don’t realize that they may not be able to repeat them even though they now have experience from that one great achievement. What more for the rest of us who learn from their experience second-hand via their writings?

How useful are the general conclusions drawn from a small sample size of achievements?

16/ "We confirmed this paradoxical aspect of the system by running a powerful computer program for thousands of generations. First, we chose a target image from those that users have discovered and published on the site. Then, at every generation the program automatically chose parent pictures that look increasingly similar to the target image10. The result for the most interesting images—total failure. It’s impossible to breed an image if it’s set as an objective. The only time these images are being discovered is when they are not the objective. The users who find these images are invariably those who were not looking for them."

A limitation to the objective-based search. The next few highlights go into the specific reason for the limitation.

17/ "We expect an “A” student to know more about chemistry than one who is failing the class.

To borrow a term from computer science and optimization theory, this kind of measure is often called the objective function. Of course it’s no surprise that this term includes the word “objective” within it: It’s literally a method to measure progress towards the objective. So if we say that the objective function is improving, it means that our measure of progress suggests we’re moving closer to the objective. But here’s the problem: The idea that an improving score guarantees that you’re approaching the objective is wrong. It’s perfectly possible that moving closer to the goal actually does not increase the value of the objective function, even if the move brings us closer to the objective.

…Recall that the predecessor to the Car was the Alien Face. If our objective function for obtaining a picture like the Car is “how car-like is it?” then the Alien Face would be graded poorly because alien faces are definitively not cars. But the Alien Face in fact was the stepping stone to the Car, which shows you why always comparing where you are to where you want to be is potentially dangerous."

The Problem is Deceptive Stepping Stones

18/ "This situation, when the objective function is a false compass, is called deception, which is a fundamental problem in search. Because stepping stones that lead to the objective may not increase the score of the objective function, objectives can be deceptive.

… To make this idea more concrete, there’s a great example of this kind of deception called the Chinese finger trap.

… The deception of the Chinese finger trap is that the path to freedom is to push inward, away from freedom. In other words, the stepping stone to freedom is to become less free.

… The Chinese finger trap has only one deceptive stepping stone. There’s almost no question that ambitious problems like designing artificial intelligence or curing cancer will require well more than a single deceptive stepping stone. In fact, the search space of any complex problem is sure to be littered with deceptive stepping stones."

From a career perspective, making less money, earning less prestige, or simply having less immediate job security in order to free up more time or regain autonomy are all possible deceptive stepping stones towards actual wealth.

19/ "Consider for example the game of chess: There are many moves that seem promising (such as capturing a piece) that later actually lead to trouble because of subtle unforeseen implications. As tricky as that makes chess, the world we live in is far more complicated than even that, so deception is going to be everywhere. The moral is that we can’t expect to achieve anything great without overcoming some level of deception."

20/ "… any problem without deception is trivial, because the stepping stones to solve it would be obvious. Clearly that is not the case for our most ambitious objectives, because we have yet to solve them. That’s why deception is so universal.

… Deception is the key reason that objectives often don’t work to drive achievement. If the objective is deceptive, as it must be for most ambitious problems, then setting it and guiding our efforts by it offers little help in reaching it."

21/ "If we go back to Picbreeder for a moment, one of the most interesting things about it is that it has no final objective.

…There’s a better way to think of Picbreeder—as a stepping-stone collector. It collects stepping stones that create the potential to find even more stepping stones.

Collecting stepping stones isn’t like pursuing an objective because the stepping stones in the Picbreeder collection don’t lead to somewhere in particular. Rather, they are the road to everywhere. To arrive somewhere remarkable we must be willing to hold many paths open without knowing where they might lead. Picbreeder shows that such a system is possible."

Going after passions that have the potential to help you collect more passions is a more poetic way of what I wanted to say with my virtuous cycle diagram from earlier.

I recall how the late Kobe Bryant was first a basketball NBA champion and then an Oscar winner for best animated short film. Definitely a lot easier to get movie people taking your calls about making a short film when you’re leveraging your status as a celebrity NBA champion.

Another way Kobe Bryant leveraged his past achievements into the award winning film is that the film itself is about his love for basketball. So, it talks about a topic he was intimately familiar with.

22/ "Let’s try a thought experiment to see what happens when objective thinking is applied to natural evolution.

…Your objective is to evolve organisms with human-level intelligence by selecting which organisms should reproduce. The basic idea is to replace natural selection with your own decisions about who gets to reproduce. For example, if you happen to spot what looks like the Einstein of amoebas, you can select it to reproduce and make more amoebas like it.

… The great thing about this experiment is that we know it’s possible because those very single-celled organisms did evolve over billions of years into human beings.

… So what should be your strategy to breed single-celled organisms all the way to human-level intelligence? We’d like to suggest a clear-headed approach that gets right to the heart of the matter: You can administer intelligence tests to the single-celled organisms! Then all you need to do is pick the ones that score highest to be the parents of the next generation. Soon enough, we’re on our way to a real Einstein, right?

… The problem is that the stepping stones to intelligence do not resemble intelligence at all. Put another way, human-level intelligence is a deceptive objective for evolution.

… subjecting a cell to an IQ test (or any intelligence test) is unquestionably ridiculous. But the fact that it is ridiculous is exactly the point, and is why this experiment should ring alarm bells for anyone who still believes in the myth of the objective."

23/ "Like Picbreeder, evolution in nature is a stepping-stone collector. These stepping stones are collected not because they may lead to some far off primary objective, some ultimate uber-organism towards which all of life is directed, but because they are well-adapted in their own right."

“Well-adapted in their own right” is a great criteria for selecting which passions to pursue and maintain. Either they are low in costs or they are at the very least self-sustaining. The moment they are self-sustaining, then you basically have near unlimited runway for any one of them to break out.

Psychologically, I also found that doing things in an autotelic sense, is crucial for keeping the passion “pure”. It needs to be pursued for its own sake. Not just because it may one day turn into something lucrative.

Minimum Criterion and Other Constraints

24/ "… it’s common to believe that evolution does have an objective, which is to survive and reproduce.

… how often is the product of an objective-driven effort not the objective? Birds are a product of evolution but birds were not the objective. Nowhere in survive and reproduce does it say anything about birds. Would any entrepreneur start a company with the sole objective of creating a product that lasts a long time?

… Usually, the objective is a well-defined product that you ultimately do produce if you are successful, not a nebulous generality.

… Usually, when we formulate an ambitious objective, we haven’t already achieved the very objective that we’re setting. setting. That would be a rather odd way to start. What kind of strange marathon is over exactly when it begins? But that is precisely how survive and reproduce works: Clearly the very first organism on Earth survived and reproduced, or we wouldn’t be here. Not only that, but then so did every other organism from the very beginning in the direct chain through the tree of life that leads to us.

… Is that really objective-driven discovery in the traditional sense?"

For the authors, that they have a highly precise definition of the word, “objective”. It cannot be some “nebulous generality”. It refers to a well-defined, specific, and concrete outcome. And it clearly can only be achieved at the end of the endeavor.

The rigor displayed in this thinking impressed me. No wonder the authors are scientists. This is the level of rigor I want to emulate in both my work and my writing.

25/ "Perhaps survive and reproduce can be more naturally seen as a constraint on evolution. In other words, it’s a kind of minimal criterion that all creatures must satisfy to continue evolving. But it describes nothing about the products that might be created, nothing about the difference between where we are today and where we might be tomorrow, and nothing about the potential for greatness lurking behind it. And by viewing survival in nature as a constraint rather than as an objective we no longer have to bend words in unnatural ways."

The authors took “survive and reproduce” and flipped it from an objective of evolution to being a constraint on evolution.

This makes me think how many of the “goals” I set out for my own one person software business such as revenue levels are perhaps framed incorrectly. They should have been treated as “constraints” instead.

26/ "Almost no prerequisite to any major invention was invented with that invention in mind.

… Great invention is defined by the realization that the prerequisites are in place, laid before us by predecessors with entirely unrelated ambitions, just waiting to be combined and enhanced. The flash of insight is seeing the bridge to the next stepping stone by building from the old ones."

27/ "Even if your goals aren’t particularly noble, you can’t avoid the problem of deception. Maybe you just want to become rich. But as we saw from the personal stories in the last chapter, measuring success against the objective is likely to lead you on the wrong path in all sorts of situations. Deception applies to becoming rich just as everywhere else."

I know a childhood friend did a bunch of career changes on his way to running a million dollar business. Ranging from being a regular in the military to being regional sales for a German manufacturing company to now running his own interior design agency. He didn’t even make some of these choices out of passion. Sometimes, it was the very thing that he could make a living in.

I recall he had an extremely rough first 18 months in his interior design agency business. He quit his lucrative regional sales manager role to pursue this only because the sales manager role required him to travel a lot and he wanted to be more available for his elderly parents.

Deception is very real even for highly mundane goals like getting rich and doing well in career.

28/ "We should be concerned by the disconnect between how the world is supposed to work and the way it really does work. When we set out to achieve our dreams, we’re supposed to know what our dreams are, and to strive for them with passion and commitment. But this philosophy leads to absurdities if taken literally. You can’t evolve intelligence in a Petri dish based on measuring intelligence. You can’t build a computer simply through determination and intellect—you need the stepping stones. You can’t become rich simply by seeking a higher salary—getting a raise today doesn’t guarantee another raise will ever come in the future. There’s much we cannot achieve by trying to achieve it."

I will do a Part II on the Notes on Objective Paradox in future. So stay tuned.

D. Betsworth and J. Hansen, “The categorization of serendipitous career development events,” Journal of Career Assessment, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 91–98, 1996. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/106907279600400106

J. Bright, R. Pryor, S. Wilkenfeld, and J. Earl, “The role of social context and serendipitous events in career decision making,” International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 19–36, 2005. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10775-005-2123-6

D. Lawrence, The complete poems of DH Lawrence. Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1994.

S. Otfinoski, Calvin Coolidge. Marshall Cavendish Children’s Books, 2008.

K. Ginsburg et al., “The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds,” AAP Policy, vol. 119, no. 1, p. 182, 2007.

A. Rosenfeld, N. Wise, and R. Coles, The over-scheduled child: Avoiding the hyper-parenting trap. Griffin, 2001.

F. Levy, 15 Minutes of Fame: Becoming a Star in the YouTube Revolution. Penguin, 2008.

J. Livingston, Founders at Work: Stories of Startups’ Early Days. Springer, 2008.

D. Sheff, Game over: how Nintendo zapped an American industry, captured your dollars, and enslaved your children. Random House Inc., 1993.

B. Woolley and K. Stanley, “On the deleterious effects of a priori objectives on evolution and representation,” in Proceedings of the 13th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, pp. 957–964, ACM, 2011.

Seeing overtones of Moloch vs Slack, RH vs LH, Relevance Realization in here. Also Small Bets, Daniel's latest newsletter has similar themes.

https://newsletter.smallbets.co/p/imagination-is-overrated