The Specific 003: Luck

🍀🍀🍀🤞🤞🤞🧧🧧🧧

Hello friend,

Recently, I was chatting with Edwin on Twitter when I shared that I have a multinational company (MNC) customer paying me 7.5k USD monthly for my software services.

Right away, he asked how I got my first customer for my service business:

Here is my response and how I got my first customer:

if I hadn't attended my old friend's birthday party…

if the customer had not changed their CEO…

if the new CEO hadn't set out the mandate to automate everything...

if the customer’s Singapore ops team who knew me since the previous CEO and had not stayed together into the new CEO tenure…

if the Philippines office hadn't required the Singapore office to intervene...

if their in-house IT team was efficient in the first place...

I wouldn't have the contract and leverage I have today with this particular customer.

I had a lot of lucky breaks, 6 by my count. He agreed, but also pointed to how I made my own luck. This little exchange encapsulated for me the two most common ways to look at luck.

The two most common ways of looking at luck is:

It’s all dumb luck. End of story.

Luck is just perseverance and making the randomness work for you.

I get the appeal of each narrative. But, both are cherry-picking.

The “it’s dumb luck” fixates on the randomness of reality but denies the importance of efforts. While the latter fixates on efforts but conveniently ignores how outcomes vary even with same efforts by different people. The truth is, there’s always a mix of both.

So I thought, maybe I should dig a bit deeper.

And I did and found this 1979 paper (The Varieties of Chance in Scientific Research by J H Austin) which had more granular and more interesting categories on luck

The following is my modification of the original table in the paper.

Table Representing Kinds of Luck

Find Your Personal Fit

Let me try to map the conversation between Edwin and myself into this table.

Type I Blind Luck: Me listing out the 6 lucky breaks

Type II General Exploratory Behavior: Edwin pointing out the efforts I have put in (and also available to anyone in my shoes) in between all those lucky breaks.

Type III Sagacity and Type IV Personalized Action are much harder to bring to mind. And also the more interesting, because they help explain why no two success stories are exactly alike.

They are like the product-market fit concept in startups. Using that analogy, both sagacity and personalized action are like person-action-worldview fit.

It’s like how not everybody who practice as much as LeBron James will end up exactly like him. A small minority who do so might turn out to be NBA stars as well, but they will be their version of an NBA star. Not a LeBron James clone.

Replace LeBron James and NBA star in the previous paragraph with a different high performer and accolade, and the pattern will largely still holds true.

Returning to my personal experience of having 6 lucky breaks to secure the customer, if I were not the right fit, or did not have the right skills to create value, no amount of lucky breaks would have helped me.

My personalized efforts and idiosyncrasies such as:

my preference to take on new challenges, (I score slightly above average for Openness to Experience)

my tendency to look at a problem from both software development and business analysis viewpoints, (A developer who worked with me once called me a “business coder”)

my willingness to accept less stability for greater variance in outcomes (hey, I run my own biz 🙃)

were factors too.

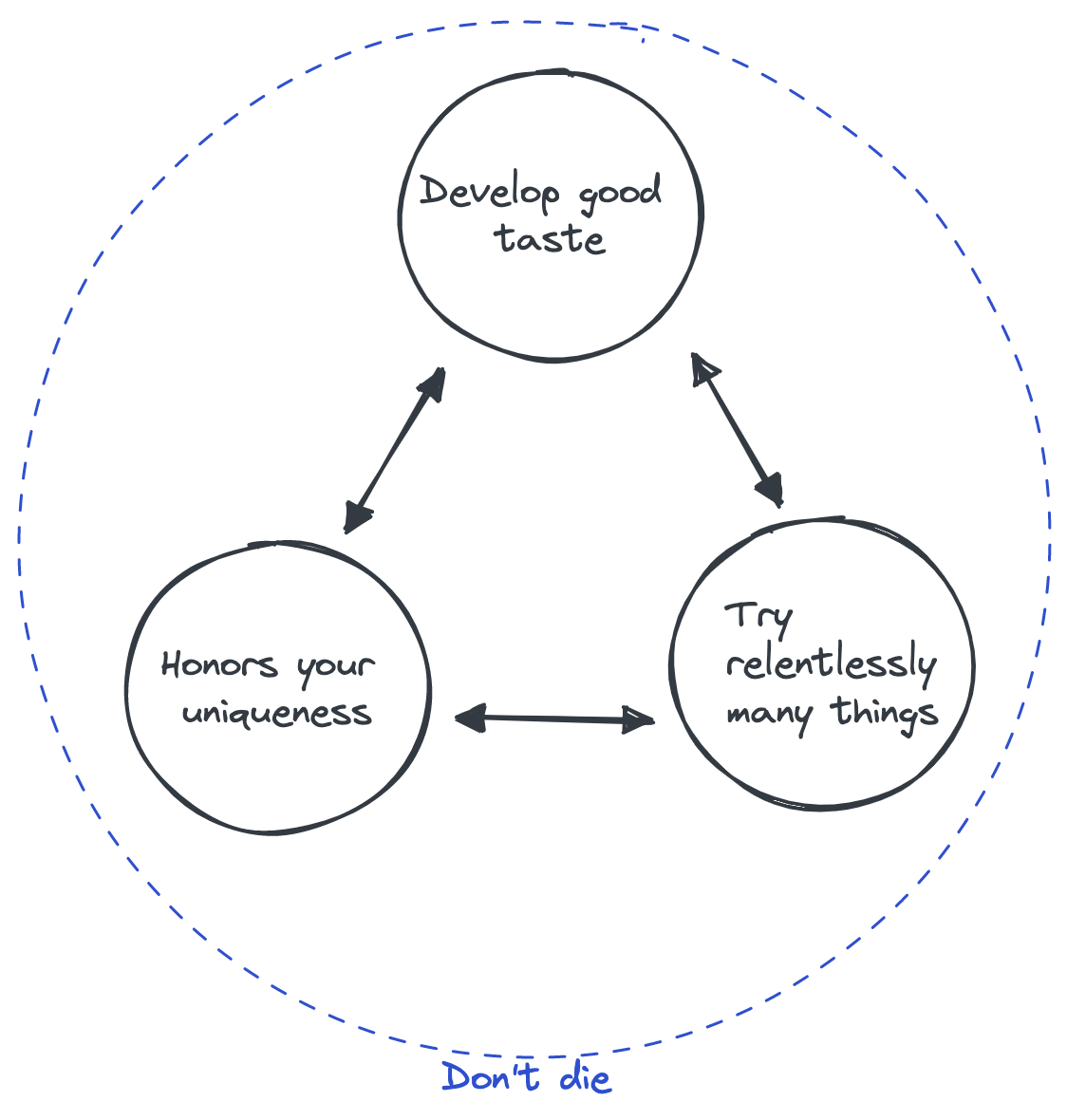

If I were to reformulate for luck, I would say:

Develop a taste for what’s good

Be determined and relentlessly try many things

In a way that honors your uniqueness and aligns with your taste

Don’t die trying

Not as catchy as “make your own luck” and “it’s all dumb luck” cliches.

But I prefer this level of precision and nuance anytime of the week.

Elsewhere On The Web

A tech billionare told me his founder story

Coincidentally while writing about luck, I came across this thread by Lance Sun about an anonymous tech billionaire.

Notice the complete absence of any buzz-wordy frameworks or sappy coherent narratives about passion or perseverance.

And as Lance summarized at the end, survival is key.

“Don’t die” is probably the most universal advice in the messy world we live in.

I want to thank Chris Wong, Louie Bacaj, Greg Lim and Sam Cho for reading drafts of this. And Edwin Tan who asked me thoughtful questions via Twitter DM and giving permissions to share our conversation.

P.S. you can respond directly to this email. I read every reply. I'd love to hear from you.

Great work here mate! Loved the read 😃