Two Kinds of Wrong Abstraction Level (21/30)

I'm writing 30 posts in 30 days. This is number 21.

Cedric Chin wrote about choosing the right abstraction level when talking about ideas. I like to talk about two ways it can be wrong.

Axes of Precision and Abstract/Concrete

Imagine two axes: Precision and Abstract/Concrete. I represent both precision and abstract/concrete as axes with dimensional values for now. Dimensional values are values that lie on a spectrum, say 0 to 100. As opposed to categorical values. Categorical values have a “either you’re in or you’re out” sense to them. You either belong to a category or you’re not. There’s no in-between. Imagine that it looks like this:

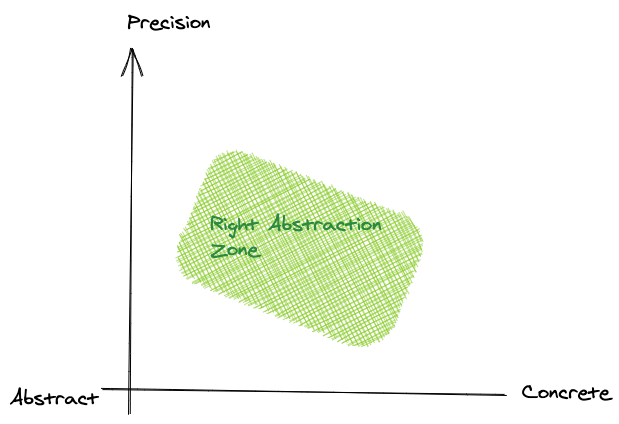

Now imagine we declare that the right abstraction level lies in the shaded area.

Now each axis will tell us when we get our abstraction level wrong.

We can be too precise (or too much details) and not precise enough (or too hazy) on the precision axis

We can be too abstract or too concrete enough on the Abstract/Concrete axis.

Now, at this point, you might feel the mistake of being too abstract feels the same as being not precise enough. Similarly, too concrete feels the same as too precise. Yes, when you make the mistake of being too abstract, you tend towards being too imprecise. Actually it’s possible to be both too abstract and too precise. E.g. you construct a highly elaborate fantasy model to explain certain phenomenon. It’s rare but it can happen.

How about “too hazy and too concrete”? An example I like to put in this category would be when you overly rely on the emotions borne out of past experiences to do your thinking for you. There’s concrete examples ( your past experiences with, say dogs) which gave rise to your current strong emotions (for example fear) and you simply took actions that overly compensate. Such as going out of your way to avoid dogs even metres away. I admit I haven’t really thought hard about this, and if you have a good argument, I will readily remove this as a valid category.

These Mistakes Can Overlap

Being too abstract tends to be associated with top-down, deductive thinking. You start with a general theory and try too hard to make it fit into any and all specific case. You conveniently ignore the relevant details that don’t fit into the abstraction while you overly emphasize the details that do. That’s the danger of being too obsessed with abstract theories over real-world relevant details. This is how being too abstract leads to being too hazy.

Being too concrete tends to be associated with bottoms-up, inductive thinking. You start with specific cases. Particularly those in your personal history. You try to draw too much pattern from these specific experiences. Instead of overly fit new cases into an abstract theory when you’re too abstract, here you can overly fit new cases to the lessons drawn from past cases. This is how being too concrete leads to being too precise (on the wrong details).

And it’s entirely possible to be both too hazy and too precise in your analysis. You get too hazy on details that require more precision, and too precise on details that don’t need that much precision.

Given how some of these different abstraction mistakes can overlap in the same situation in different combinations, I prefer to think as only two ways of mistakes. This is what I consider as the right abstraction level to think about wrong abstraction levels.

Which I’m repeating here as:

We can be too precise and/or not precise enough.

We can be too abstract or too concrete enough.

And there’s nothing that says both mistakes are exclusionary.